REVISION: I have floated the revised analysis I am posting here for several years, but have not, till now, published it on this blog. I stated it publicly in April 2016, on location, in the presence of NPS Historian John Heiser, and numerous other attendees. I am very convinced that the dead seen in these images are members of the 151st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Initially I would have thought them to be the dead of the 24th Michigan, but what I understand now shows me that the Iron Brigade skirted to the north of this location, falling back, past the 151st Pennsylvania who were going to take the brunt of Virginia and North Carolina units pressing through the woods. The 151st Pennsylvania made their stand on the crest, in front of the edge of the woods where Reynolds fell, until falling back across the field bordered by fences to the north and south. This field is the reason why the "Field Where Reynolds Fell" captioning is derived by Gardner. I am officially publishing this revision on

10/12/2018.

Be sure to read the post attached to our February 25, 2013 link. Click here. It further demonstrates this site is located on the first day's field. Clear visual evidence.

This post has been revised to reflect the corrected findings of my October 6, 2012 return visit.

Be sure to read the October 12, 2012 post on this subject by clicking here. It contains more current information on the location.

Additional information can be found on the June 14, 2012 post by clicking here.

One of the most elusive group of Civil War battlefield photographs has been the image known as “The Harvest of Death” and its companion images, showing the same bodies from a near opposite angle. The group was made in the days following the battle, most probably July 6, 1863. There have been three prevailing theories as to the precise location of this ghastly scene.

Since 1975, historian William A. Frassanito has felt comfortable in his belief that the group of photos was taken somewhere near the Rose Farm and the Emmitsburg Road. The greatest challenge has been in trying to locate a piece of land where all terrain features cooperate, in both directions, to make the theory work. Granted, doing this has been made even that more difficult by over a century’s growth and/or removal of wood lines and other obstructions, as well as potential modifications to the landscape surface. The mission has continued for another thirty-seven years as numerous investigators have scoured the battlefield landscape to find the right combination of elements.

Gardner caption, "View in field on right wing."

Library of Congress collection.

In May 2011, Gettysburg National Park Service Historian

Scott Hartwig published his own theory, located in an area below the Chambersburg Pike, near McPherson’s Woods that seemed to work, and was much more in keeping with the original captioning of the published images by photographer Alexander Gardner. It runs along the Park Service road, Reynolds Avenue South.

Most recently, historian

Jerry Coates has spent considerable time investigating an area south of Gettysburg, and west of the Emmitsburg Road. This theory stayed more within the confines of the original Frassanito analysis, but was supplemented by a more in depth study of the uniforms the dead are wearing and attempting to use this criteria to narrow down the numerical potential as to who they might have been and thus the field of battle these men would have been engaged on in July 1863. He has come up with very similar terrain and some good arguments.

However, my own investigative work has concluded that of all these prevailing theories, the one that seems to come the closest is Scott Hartwig’s on the first day’s battlefield. But, although very well founded and assembled with sound judgment, Hartwig’s theorized location has its faults and can be termed with the old expression, “Right church, wrong pew.”

What all the prevailing theories lacked was a concrete feature or landmark that would anchor the image to an indisputable location. My examination of the series of images has discovered what appears to be that necessary clue. The clue has been available in plain sight to all that have looked at the glass negatives for the stereo pairs, and quite possibly the 8 X 10 glass negative, although that full image is not printed or available online presently by the Library of Congress, but is referred to by William Frassanito and shown in cropped form on page 227 of his

Gettysburg: A Journey In Time. In many prints of the image entitled “Field where General Reynolds Fell”, the full image has been cropped and has thus removed the landmark feature. The landmark looks like none other than the residence of Mrs. Mary Thompson, known more famously as “Lee’s Headquarters”. In the upper right hand corner, again invariably cropped out in published formats, the house is easily discernible along the horizon line. It is understandable that it could be easily overlooked as just another shadow in the line of trees, but when magnified, and compared to wartime images of the structure, it becomes more than obvious. In utilizing the Thompson house as the anchor for this image, it becomes far easier to establish a camera position, and thus, possibly prove that Gardner’s original captioning was spot on as to the vicinity of the battlefield.

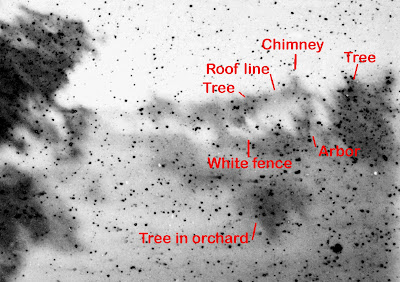

Is this the home of Mrs. Mary Thompson, "Lee's Headquarters,

as seen in an enlargement of one half of a stereo glass negative?

Annotated copy of the previous enlargement showing key elements.

Find these same elements in the image below for comparison.

All images are clickable for enlarged viewing.

Photograph of Mrs. Thompson's house, attributable to Mathew Brady.

Note the white fence, chimney, and trees on either side of the building compared with

those features in the enlarged views preceding. Is this the rock solid clue to these images?

Library of Congress collection.

Overlay with Thompson house image by Brady at 75 percent

transparency over top shadows seen in Gardner image, right horizon line.

Brady's street level image was of course taken close up, but even at

464 yards, the shape of the house and surrounding trees is discernible.

Two field reconnaissance trips to the Gettysburg field had given me the evidence to support this theory. On November 18, 2011 and January 11, 2012, my investigations concluded that the dead in this series of exposures were likely killed south of the Chambersburg Pike, between McPherson’s Ridge and Seminary Ridge. This section of the field was just below the northernmost of two fence lines that ran parallel to the Pike and enclosed a field that included the Herbst Woods in its western extreme. If so, these men fell approximately 100 yards east of the spot marked where General Reynolds fell, and roughly 460 yards southwest of Mrs. Thompson’s house. The camera location is roughly 290 yards northeast of Scott Hartwig’s theorized conclusion, which was south of the lower enclosing fence, and too far south of the Thompson house to have allowed for the structure to appear as it does in scale along the Chambersburg Pike Ridge. Jerry Coates theoretical location is approximately one and three quarter miles south of the Seminary Ridge killing field.

Gardner's camera position adjusted October 6, 2012 with further corrections October 12.

Click on this and all images to enlarge.

Green triangles indicate approximate field of view of lens for both images.

Light tan lines indicate approximate war-era fences separating field.

The Gardner image, note the faint Thompson house at upper right, along horizon.

Approximate same view as of October 6, 2012. Thompson house to right of motel complex.

Gardner's "Harvest of Death"

See my September 28, 2012 posting regarding the horizon line and

apparent doctoring of the image by Alexander Gardner.

Approximate same view as of October 6, 2012.

Initial investigation, and attempt to set up the shot towards the Thompson house.

Seminary Ridge is in the background. November 18, 2011.

Photo by James Anderson.

Looking for the correct view toward the Thompson house on November 18, 2011.

Photo by James Anderson

Be sure to visit the June 27, 2012 post

for the complete story

Monument to the 24th Michigan overlooking

Willoughby's Run. January 11, 2012.

These men, and others of the Iron Brigade, exited this area, and fled past the

151st Pennsylvania who would cover their retreat, taking heavy casualties.

Mrs. Thompson's house as it appeared January 11, 2012 with the addition of

dormer windows expanding the second floor. At the time of this photograph

the home served as the Lee's Headquarters Museum.

View of the field from Reynold's Avenue South, June 14, 2012.