O'Sullivan's stereoview, looking northwesterly, at about 10:13 A.M., Civil War time.

The view today, 150 years after, at 11:24 A.M., modern time.

O'Sullivan's southwesterly view, somewhere probably before or after the previous image.

I hesitate to place a time on this image, outside of the date, with any certainty, due to the

lack of strong shadows cast on the building. The large tree, and the figures are silhouetted,

giving indication that the sun is most likely in the same position as in the previous view, but...

...here is a modern view, taken at 11:28 A.M., modern time, under an atmospheric

condition alluded to at the top of this post. What had me wondering, and I do

speak of it in the video below, is the absence of strong shadows in the period

image. And amazingly the answer presented itself, right as I set up to take the

present day view. Clouds! Scattered clouds blocked the sun right when I needed

them, and demonstrated that O'Sullivan was working with the same conditions.

The cloud cover creates a diffused light, softening the contrasts on the building walls.

And in this view, taken at 11:29 A.M., a minute later, the sun has again emerged,

showing that indeed the strong shadows are again revealed. After that the clouds

pretty much burned off for several hours. I certainly felt blessed. Mystery solved.

Here is a full frontal view of the church, looking slightly southwest, taken at 11:25 A.M.,

modern time, which would approximate at 10:14 A.M., Civil War time, showing the

configuration of the shadows seen in the first O'Sullivan view, at top. In the video

below, I go into a brief discussion of where the shadows fall on the easily

countable courses of brick in the 1864 images. For all intents and purposes,

we are looking at Bethel Church at exactly 150 years after O'Sullivan's images.

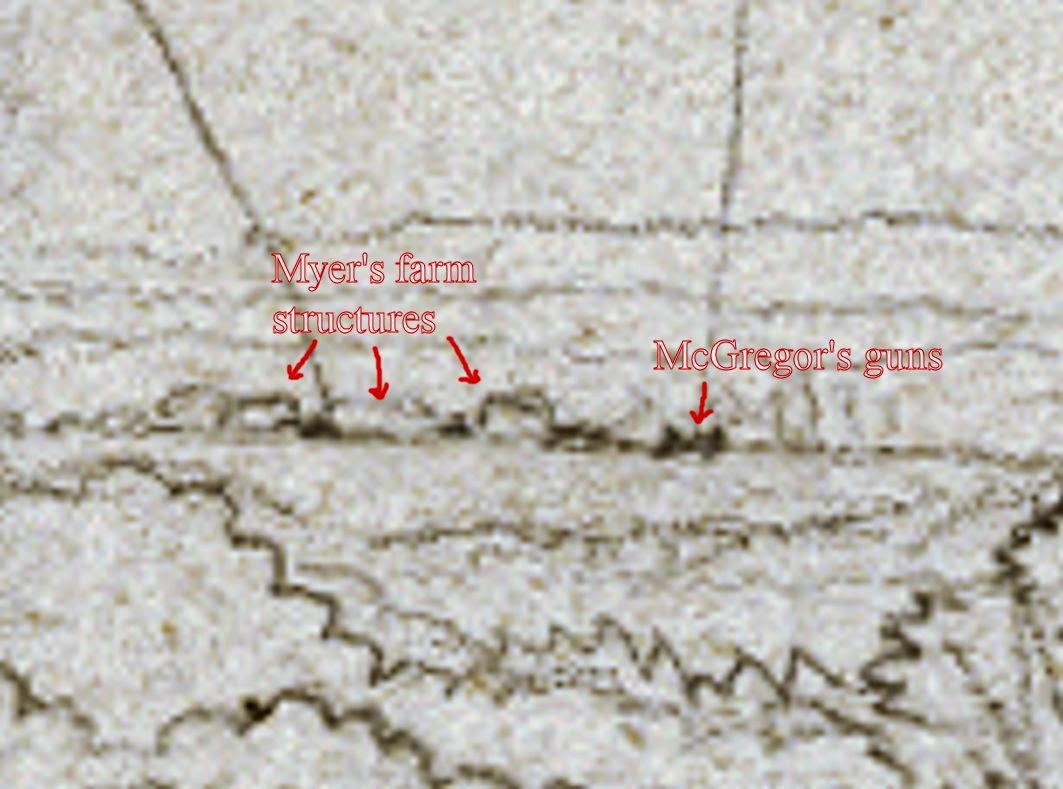

Enlarged detail, with adjusted contrast, to reveal the shadows of approximately,

10:13 A.M., on the morning of May 23, 1864, as photographed by O'Sullivan.

Compare with the modern image seen above the video.