The principles of tissue depth, in this case along the median points of the skull, are the building blocks for forensic facial reconstruction. These points: vertex, glabella, naison, rhinion, sub-nasale, labrale superius, labrale inferius, mentolabial sulcus, pogonion, gnation, menton and gonion, provide us with a reasonably reliable, statistically established, method of creating the outline of a deceased's facial profile.

This then, was an exercise for me, to apply these basics on one of the many skulls collected by Union Surgeon, Dr. Reed B. Bontecou, in April of 1866. Bontecou traveled to the battlefields of Spotsylvania County, shortly before mustering out of the service, with the intent of collecting pathological specimens, specifically the crania of dead Confederate soldiers who's remains had been lying in situ since the battles nearly two and three years prior. The Union dead had been gathered and placed in temporary cemeteries in the summer of 1865. In contrast, many of the fallen southerners had been barely covered by comrades, and their bones bleached in the sun while their uniforms decayed around them. The region had been devastated by the war, and a dramatically reduced local population had yet to make any effort to provide better treatment, especially in such remote areas as the Wilderness.

This specific individual had received a severe trauma in the vicinity of the left ear, producing a large, fractured hole in the temporal area, but no exit wound. A good number of these skulls in this collection have the deadly projectile which ended their lives accompanying them, usually attached by wire near the entry site. This specimen does not.

NMHM collection # AFIP1000619

Site of the fatal wound. Note extra tooth growing out of left maxilla.

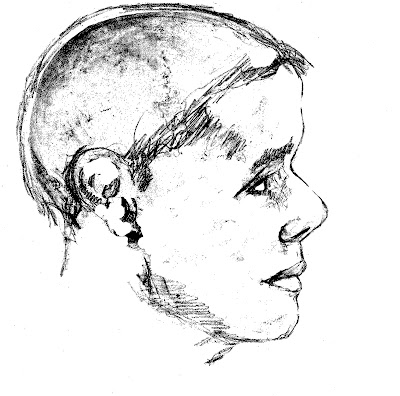

My initial workup over top the right profile photograph, having used

tissue depth markers to establish the outline of the face.

The base photograph and drawing are reduced to line art.

After removing most of the base photograph and refining the

facial features we are left with what may be a faithful likeness

of this unknown soldier, killed in Spotsylvania, Virginia.

Of course, we do not know if he had facial hair or precisely what age he was. A more professional working of the specimen can yield many more tell-tale clues to these details. Perhaps one day the funding may become available to the Museum to help put a face on all the unknowns that reside in the drawers of the collection. No matter what the circumstances that brought this man's life to an end, all should be accorded the dignity of recognition as a human being. I hope this may be some encouragement toward that goal.

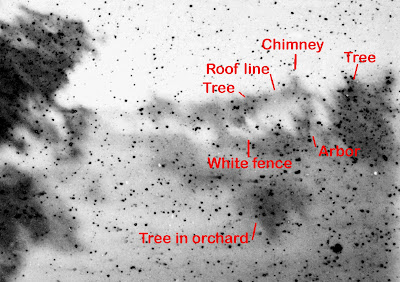

A photograph taken of human remains during Dr. Bontecou's trip to Spotsylvania County

in April of 1866. Bontecou had a photographic team accompany him on this journey. For

further information, I will suggest an article I wrote for the March/April 2009 issue of

Civil War Times Magazine, introducing my studies of these images and the route taken

by Bontecou and his entourage. I continue to work on a book length manuscript as well.

In September 1865, Northern journalist John T. Trowbridge toured the war-torn Spotsylvania region with a local guide, and witnessed the same unburied bodies Dr. Bontecou would find nearly a year later. From his book The South: A Tour of Its Battlefields and Ruined Cities, he describes his macabre encounter in the Wilderness region:

"And what appalling spectacle is this? In the cover of thick woods, the unburied remains of two soldiers -- two skeletons side by side, two skulls almost touching each other, like the cheeks of sleepers! I came upon them unawares as I picked my way among scrub oak. I knew that scores of such sights could be seen here a few weeks before; but the United States Government had sent to have its unburied dead collected together in the two national cemeteries of the Wilderness; and I hoped the work was faithfully done.

"They was No'th Carolinians; that's why they didn't bury 'em," said Elijah, after a careful examination of the buttons fallen from the rotted clothing.

The buttons may have told a true story: North Carolinians they may have been; yet I could not believe this to be the true reason why they had not been decently interred. It must have been that these bodies, and others we found afterwards, were overlooked by the party sent to construct the cemeteries. It was shameful negligence, to say the least.

The cemetery was nearby -- a little clearing surrounded by a picket fence and comprising seventy trenches, each containing the remains of I know not how many dead. Each trench was marked with a headboard inscribed: "Unknown United States soldier, killed may, 1864."

Elijah said that the words United States soldiers indicated plainly that it had not been the intention to bury Rebels there. As a grim sarcasm on this neglect, somebody had flung three human skulls over the paling into the cemetery, where they lay blanching among the graves."